Written by Diane

Arrieta

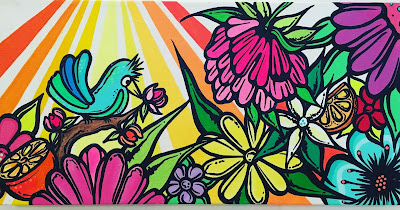

Dana Donaty. Maestro.

Acrylic on canvas. 2016

When you first encounter the

work of Dana Donaty, you are hit with a profusion of color and fairytale-like narratives

that explode on her canvases. It takes a while to settle into one of her

paintings. But when you do, you can get lost for hours discovering the

characters and the stories summoned by her stockpiled memories. How did they

get there? Do they exist outside of Donaty’s paintings and imagination? Why are

some of them so familiar to us?

To

examine how her character art becomes transformed into picture, there are two

important aspects of the work that must be examined: the how and the why. Many

artists focus on the “how” they make their art, while others focus on the “why”

they make their art. Donaty’s work demands viewers to examine both the how

and the why. The process and the purpose of her work are rooted in her cultural

identity of growing up in an American nuclear family. This idea is very

apparent when studying the work of artist Jaune Quick-to-See Smith. Her

cultural identity and socio-political views are embedded in her art and cannot

be separated (Quick-to-See Smith, 2019). Although Donaty employs a more subtle

approach with her social views, the how and the why should not be separated when

considering Donaty’s work.

An overview of Character Art:

Character art refers to an original figure that an artist,

illustrator or animated film designer creates from scratch. The concept, style,

physical characteristics and personality traits of the character (human or

otherwise) are all decided by the designer. Developing a new character requires

the artist to embark on “a creative dive into the unknown and from the abyss,

pull out a new design” (Concept Art Empire, 2019).

There is no wrong way to approach character development,

and each artist or designer settles into their own methods. They gain

inspiration everywhere from animated film, television, advertisements, cereal

boxes, and more (Creative Blog, 2019). Designing a 2-D character is slightly

different than designing for an animated 3-D film. For a painting, the artists

needs to consider one angle. A 3-D character requires the character to be seen

from all angles. One interesting aspect of Donaty’s art is that her characters

begin flat in the painting; however, she also explores bringing them to life

outside of the painting into the 3-D realm. One of her first characters that

has made the leap outside of a painting is Captain Money Pants (shown below).

Donaty is currently working toward bringing several of her characters to life

by means of a variety of different mediums.

Captain

Money, Pants. Mixed Media. 2017

The How:

Indulging a Donaty painting begins with exploring her

unique process of employing Visual Pareidolia. “Pareidolia is the interpretation of previously

unseen and unrelated objects as familiar due to previous learning” (Akdeniz, et

al., 2018). Pareidolia in the visual arts has been discussed since the time of

Leonardo da Vinci (McCurdy, 1923) and is still in use today by several

contemporary artists. Artist Gigi Chen, an animator and painter uses nature and

urban artifacts when she engages her version of pareidolia to her work (Chen,

2019). Italian artist Maggio uses coffee stains for the base of his work

(Maggio, nd) and Illustrator Keith Larson also develops characters out of

inanimate urban objects he encounters (Marini, 2017).

The scientific reasoning for the phenomenon of pareidolia

stems from the fact that our brains use parallel processing. We find patterns

and make associations that are sifted through our memory. This is an active

constructive process. We quickly find a possible match and assign it a name.

For example when you see a duck in the clouds. You assign it that name, and the

brain fills in the details to make the cloud resemble your assigned name for it

(Allen, 2018).

Donaty’s process begins each painting with a large canvas

on the ground used as a drop cloth where splattered paint, offloading of

brushes and dirty water are all caught on this blank canvas as she paints on a

separate canvas above it. The backstory of this process relates to her

practical physician father and his “waste not want not” conditioning of Donaty,

when she worked in his medical office as a child. Because of her upbringing,

she now recycles everything. This has had a direct influence on her art

practice and character development.

The process of employing visual pareidolia for her

character development, begins when she lifts the dirty canvas up onto the wall

as the base for her next work of art (illustrated below). She stands back and

starts to explore the emerging characters that form a narrative for the work.

She chalks them out and then constructs a guided storyline.

Studio shot: Dana Donaty Fine Art

Just like the visual development artists at Disney

animation studios, Donaty is a master at manipulating her pictorial environment

while her characters form an emotional connection (Disney, 2019) through her

technical prowess with a brush. She manipulates the scene to direct the viewer

on the start of a magical journey that leads wherever their own imagination and

social recall takes them. As the story develops, Donaty always adds in a larger

than life human into the mix. The characters determine the providence of her

humans within the context of the painting.

The why:

As stated above, inspiration

for character development can come from a wide variety of sources and stored

memory. One aspect to understanding the context of the character worlds found

in a Donaty painting requires consideration of the impact American

television has had on culture and society (Novak Djokovic Foundation, nd). Early

television programming during the

60s and 70s, was created for the presumed White audience. It intentionally

avoided social issues and real-life concerns in order to not offend or alienate

viewers (Encyclopedia.com, 2019). Conversely, popular in that time were

Saturday morning cartoons. Cartoons teach kids how things function in

real life, while offering ways of dealing with difficult situations (Novak

Djokovic Foundation, nd).

The most prevalent shows for

adults of that era were domestic comedies—generic, character-based shows set

within the home (UMass, 2019). Donaty was being conditioned to avoid conflict

through comedy, but was also given the license to add in social commentary, predisposed

by weekly cartoons. After interviewing Donaty in a recent studio visit, she

mentioned two main influences that were core to her childhood memory: Carol

Burnett and Charles Schultz.

Carol Burnett broke a lot of

barriers in society by starring in her own variety show, and today is viewed as

a feminist comedic hero. Not by the content or intent of her show, but by the

mere fact that she was fearless and did what no other women were doing at the

time (Duca, 2015). Donaty grew up watching Burnett’s cast of fictional

characters act out scenarios for a big laugh, week after week. I can see

similar qualities in Donaty herself—bucking the trends in the art world and

sticking with her often underestimated character world. Her paintings are a

kind of variety show with each painting a new episode of zany scenes and

characters offering Donaty’s take on society.

There have been many cultural

studies on how humor can be a tool that

helps people deal with complex and often contradictory messages in our brains

(Weems, 2014). Donaty’s paintings can be

viewed as ordered chaos. At first confusing, but looking closer, you start to

see familiar faces and text integrated into a burst of color. It offers an

entry point of exploration through a societal lens of icons and meanings

derived from our collective consciousness [Sociology Index, 2001].

Humor as

an artistic tool has been used throughout art history. When we look at the work

of John Baldessari, his humor calls attention to existing absurdities (Mizota,

2010). Artists have been using objects as joke since the infamous Duchamp

urinal, while Richard Prince recasts found objects to make us rethink how

culture operates (Lee, 2017). The one artist that gives off the same vibe as

Donaty is David Shrigley. As Lee states, his works are true and relatable as much

as they are discomforting and just plain weird (Lee, 2017). One could have

similar feelings about a Donaty painting.

Charles Schultz, creator of

the famous Peanuts comic strip and subsequent television shows, is part of most

[White] American family memories. What most people didn’t realize, is that

Schultz was very religious. “By mixing Snoopy with spirituality, he made his

readers laugh while inviting them into a depth of conversation uncommon to the

funny pages” (Merritt, 2016).

Dana Donaty. Top Dog. 60 x 48

inches. Acrylic on canvas

Many of Shultz’s comics were cryptic and

with blanks where the audience must fill in the gaps. As Merritt states, “the

result is that readers become participants of the strip’s conversation instead

of merely spectators” (Merritt, 2016). The same can be said about Donaty’s

works. They are starting points for stories that can be directed by the viewer.

We can see this in the work pictured above (Top Dog). It could have several

different interpretations. Is the human the corporate pied piper calling on the

masses to follow along, or are the characters critics analyzing the musician’s

performance? The possibilities are endless and open to interpretation. Donaty

sneaks in clever text and images that need to be deciphered by the viewer. There

is even reference [in Top Dog] to Marcel Duchamp and the Mona Lisa, with the

L.H.O.O.Q. text providing a glimpse into the understated humor of Donaty.

The characters in Schultz’s body of work

are immediately endearing. They give hope, but at the same time offer a bit of

skepticism. Donaty’s characters do the same. From

Captain Money Pants to hints of Donald Duck and Yosemite Sam, the viewer

instantly becomes reminiscent of their own childhood that these invented and

borrowed characters conjure up. The added text and scenes often have a bite

like the cynical retort found in a Peanuts comic. Schultz’s Linus character

offers up “I love mankind… it’s people I can’t stand” (Charles Schultz Museum,

2011), which falls directly into the psyche of Donaty herself.

Peanuts comics are a spectacle of little children afflicted

with adult concerns (Charles Schultz Museum, 2011). Donaty’s work may appeal to

children at first sight, but is entertaining adults with advanced topics and subtle

commentary. Just look at the sculptural Captain Money Pants’ hand gestures. Who

is that directed too? Society, the art world, nay-sayers of her work? You

decide. The reoccurring dollar signs in many of her paintings give a new layer

of context to the work. They could allude to the consumer driven cartoons and

commercials that try to sell products to children (Klein, 2010) or the money

driven art world.

Donaty’s skill at using her own unique character design

mingled with iconic characters of Disney and other relevant popular cartoons

allows a sense of nostalgia for childhood. They do their job at creating an

inviting environment to explore. Donaty offers the same journey of escapism of

the comedic variety show, while proposing the chance of a larger conversation

hidden within cartoons—for those willing to enter the mesmerizing world that is

the art of Dana Donaty.

References:

McCurdy, E., 1923. Leonardo Da Vinci S Note-Books Arranged

And Rendered Into English. Empire State Book Company, NY, New York.

Weems, Scott, 2014. Ha! The science of when we

laugh and why. Basic Books. New York, N.Y.

Author Biography

Diane Arrieta is the Outreach and exhibitions coordinator at the John D.

MacArthur Campus Library at Florida Atlantic University. She has been curating

contemporary exhibitions since 2005. Arrieta, a visual artist herself, works

with sculpture, video and illustration. She is currently exploring

environmental themes in her work. Arrieta was born and raised in Western Pa,

now living in South Florida. She holds a BFA in ceramic sculpture from Florida

Atlantic University and an MSc in Biodiversity and Wildlife Health from the

University of Edinburgh, U.K.

Artist information

Dana Donaty

Dana Donaty was raised in New Jersey, coming with a unique blend of

Colombian, Peruvian, Italian, Irish and American backgrounds. She holds a

Bachelor of Fine Arts in Drawing from Moore College of Art & Design in

Philadelphia, PA. After living in London, England for twelve years she

relocated in 2006 to Florida, where she now lives and works.